The Media Cover-Up of the Holodomor

There are several sources from the era that capture the immense pressure and self-censorship experienced by foreign journalists covering Stalin’s Soviet Union. UPI reporter Eugene Lyons provides a stunning account in his 1937 memoir Assignment in Utopia, reviewed by George Orwellhere. (From Lyons’ book, Orwell borrowed 2+2=5 for his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four). In one chapter, Lyons describes how leading journalists in the Western press in Moscow, including Lyons himself, banned together to cover-up the Holodomor in exchange for greater press access from the Kremlin. That chapter is aptly titled: “The Press Corps Conceals a Famine,” For more on that stunning orchestration of a cover-up by Western reporters and Soviet censors, listen to this interview with Nigel Colley, the great-nephew of Gareth Jones, the independent journalist who worked hard to expose the famine only to be targeted by this cover-up in an attempt to discredit his reporting.

The passage below from the memoirs of Zara Witkin, a Russian-born American who went to work in the USSR as an engineer, paints a bleak picture of Western journalistic integrity in Moscow under Stalin:

The Memoirs of Zara Witkin 1932–1934

A scene from late 1933 excerpted from Chapter XXII

“In Moscow, the foreign correspondents, watching this unprecedented, grim process, asked each other repeatedly if it were possible for a nation to raise food with bayonets. With the stories of starvation pouring into the capital, and engineers and travellers from south Russia telling of dead bodies lying in the roads, the correspondents prepared to visit these areas and see the conditions at first hand. [A reporter for United Press International Eugene] Lyons returned from Italy on August 21. He immediately requested permission to visit the Ukraine and North Caucasus. The other correspondents did likewise. All were denied the privilege by the Soviet Government. This was the first time that correspondents had been barred from a civilian area in peace-time. The government had adopted a policy of concealment!

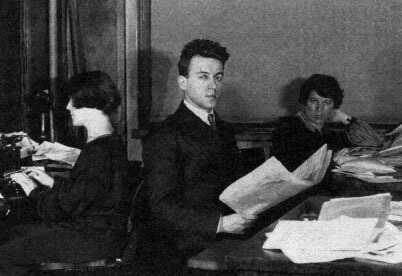

Lyons then asked the Soviet Foreign Office to select an area for him to visit—one which they were satisfied to have him see as an example. This recalled the notorious historical incident of General Potemkin, the favorite of the Empress Catherine, who hurriedly built the false ‘happy villages’ in the countryside along the route she was to take, to conceal from her the misery of the masses. This request was also denied. William Henry Chamberlin, the soft-spoken, hard-thinking correspondent of the Christian Science Monitor, who had for years taken walking trips in the Caucasus during his vacation, was now also barred from that area. While the correspondents were bottled up in Moscow, the government proceeded with its desperate effort to bring in the harvest and avoid the recurrence of the starvation early in the year. The wildest rumors of death by famine and terrible suffering of millions had reached the outside world. In a vague way the world was aware of the horrible famine which was destroying millions of lives. But the Kremlin had succeeded in confusing the issue through alibis, lying denials and frantic secrecy. The fuming American correspondents, prevented from getting or sending any of this grave news, met to consider the situation. The conference was held in the home of Ralph Barnes [of the Herald Tribune]. Walter Duranty [of the New York Times], Eugene [Lyons of UPI], [writer] Maurice Hindus, who happened to be in Moscow, and William Stoneman of the ChicagoDaily News were present while I was there. Chamberlin, Louis Fischer of the New York Nation, Stanley Richardson of the Associated Press, and Linton Wells of International News Service had been there earlier. Barnes put the question. What should be done? Their duty was to ‘get the news,’ to which access was denied by the Soviet Government. Barnes turned first to Lyons.

‘What are you going to do?’ he asked. (I knew that Lyons felt keenly about the suffering of which he was amply informed.)

‘I want to send this story,’ Lyons replied, ‘but I am blocked. I have evaded the censorship several times by telephoning ‘out.’ My agency has asked me not to antagonize the government by doing this any more. With the Soviet Government barring investigation, the censorship stopping all dispatches and my own agency not backing me, I am helpless!’

Barnes then turned to Duranty. ‘What are you going to write?’ he asked.

‘Nothing,’ answered Duranty. ‘What are a few million dead Russians in a situation like this? Quite unimportant. This is just an incident in the sweeping historical changes here. I think the entire matter is exaggerated. Anyhow, we cannot write authoritatively because we are not permitted to go and see. I’m not going to write anything about it.’ At this brutal cynicism, Lyons and Stoneman flared up. Duranty merely shrugged his shoulders and smiled, then turned to Mrs. Barnes to resume his brilliant conversation that had been so unpleasantly interrupted.

‘What are you going to write, Hindus?’ Barnes asked. ‘I am not in the same position as you men are,’ Hindus replied. ‘I do not write for a daily journal. I do not have to send any dispatches. I am a novelist. Besides, as you know, I was permitted to enter Russia this time on my definite pledge not to visit the villages. My visa was granted solely on that basis. Also, since I have not seen these conditions myself, I cannot write authoritatively about them.’

‘I propose,’ said Barnes, ‘that we demand, as a group, the permission to see these conditions.’

Stoneman and Lyons immediately expressed approval. Duranty and Hindus made it clear, however, that there could be no unanimous action. It was also recalled that Fischer, of The Nation, would not support any such suggestion. A queer light played in Barnes’ eyes and his football chin stuck out. He left the room abruptly. The other correspondents continued to converse. Under the friendly spell of Mrs. Barnes’ hospitality the ugly question was temporarily relegated to the background. Suddenly Barnes re-entered the room. His face was flushed with excitement. ‘I shot the story!’ he announced.

Consternation reigned in the room. Barnes had telephoned a sizzling dispatch about the famine despite the restrictions of the censorship. ‘What did you send?’ the men chorused. ‘I estimated the deaths by starvation to be at least a million.’ The meeting broke up at once. Barnes’ message could not fail to have the gravest consequences abroad in world opinion for the Soviet Union, and upon the correspondents themselves. The reaction, as expected, was immediate. The New York Herald-Tribune carried front-page headlines. Every paper in America queried its correspondent at once for confirmation of the frightful story. The august New York Times sent a strong message to Duranty, which in effect demanded profanely where he was when these terrible conditions were developing and why he had remained silent.

The situation forced the hand of every correspondent. They had to confirm Barnes’ daring dispatch. The Soviet Foreign Office immediately summoned Barnes and threatened him with expulsion from the Soviet Union. But the confirming dispatches of the other correspondents were now pouring across the Atlantic. Duranty the next morning in his cablegram estimated three million dead ‘of causes due to malnutrition,’ the now notorious euphemism which he coined for the famine. The Soviet Government had to expel all the American correspondents en masse, or let Barnes stay. In this dilemma it had only one practical course. The antagonism of the entire American press was too great a risk to run. Barnes remained in the U.S.S.R. on sufferance.”